The Jennings Stories

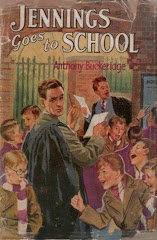

Jennings Goes to School 1950

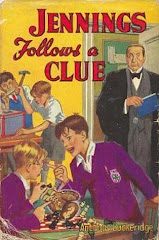

Jennings Follows a Clue 1951

Jennings' Little Hut 1951

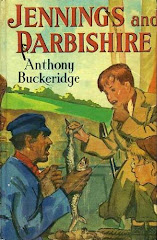

Jennings and Darbishire 1952

Jennings' Diary 1953

According to Jennings 1954

Our Friend Jennings 1955

Thanks to Jennings 1957

Take Jennings, for Instance 1958

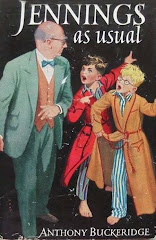

Jennings, as Usual 1959

The Trouble With Jennings 1960

Just Like Jennings 1961

Leave it to Jennings 1963

Jennings, Of Course! 1964

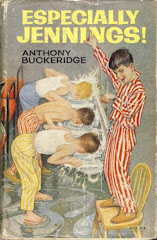

Especially Jennings! 1965

A Bookfull of Jennings 1966

Jennings Abounding 1967

Jennings in Particular 1968

Trust Jennings! 1969

The Jennings Report 1970

Typically Jennings! 1971

Speaking of Jennings! 1973

Jennings at Large 1977

Jennings Again! 1991

The Staying Power of the Jennings Stories

Written by and (c) Jim Mackenzie

My eleven year old son was on his first visit to London. After admiring the ravens on the compulsory visit to the Tower, then peering through the railings at Buckingham Palace, then later attempting to send whispering echoes round the dome of St. Paul’s and, later still, listening to the bongs of Big Ben, he and my wife ended up outside the Central Criminal Court, the Old Bailey.

“What’s that ?” he asked.

In a suitable hushed and reverential tone, trying to convey the full majesty and awe of the English legal system, my wife said, “It’s the highest court in the land.”

My son’s eyes travelled upwards and a look of contempt came into his eyes. “It doesn’t look very tall,” he said in a disappointed voice.

As we told this story against him for perhaps the thousandth time -(He is now 23 but this is what parents do to their offspring. His spelling of “banquet”, aged 8, as “bankwit” still has us holding our sides with scarcely restrained glee.) – the memory of this elementary misunderstanding took me straight back to the Jennings books. I remembered, in particular, the trouble that Jennings got into when he inadvertently called the fearsome Mr. Wilkins, “the missing link”. It was all an innocent mistake – of course – what the poor lad had noted in his diary was that Mr. Wilkins had lost his cufflink. I could recall laughing out loud when I first read it. In fact I could remember laughing a lot of the time whilst I read the Jennings books.

As we grow older the need for innocent laughter seems to increase and so I decided to take the risk of revisiting the much-loved work of Anthony Buckeridge. Was it really just a series of verbal blunders made by eleven year olds that had me and my classmates in stitches ?

I climbed the loft ladder and, after half an hour’s search unearthed a copy of “Jennings’ Diary”.

As I hauled it out from the corner where it had been wedged, a piece of glossy coloured paper fluttered to the floor from between the dark red boards. Oh, well, half a dust-jacket is better than none, I suppose. At least it was the front that I had. The old familiar characters drifted back into my mind. Surely that man in the background, belted raincoat in place, a grim, not say peeved, look on his face and a cartwheel between his outstretched arms, was Mr. Wilkins, the explosive younger teacher.

That meant that the other adult in the picture was Mr. Carter, the avuncular character, who radiated common-sense and to whom Jennings turned when he was in trouble. In the foreground are Jennings and Darbishire, with scarves of white and cyclamen pink, draped around their necks. Were they the school colours of where was it ? Oh, yes, Linbury Court Preparatory School, the small stage on which the great adventures were played out.

The mystery deepened for me. What had I and my friends, who had all attended schools run by the local council, got in common with these junior members of the privileged classes who were part of the public (private) school system ?

A silly question – after all what had I got in common with Dan Dare, space pilot of the future, with Pocomoto who rode wild horses in south-west Texas, with Just William whose family had servants and, most of all, with Biggles who flew the skies and put the world to rights ?

I slid the loft-ladder back into place, closed the hatch, returned to ground level and began to read. And the old magic worked.

The first thing I noticed was how inter-active was the nature of the writing. Take the section where Jennings first decides to write his diary in code. The code is simplicity itself for Jennings simply reverses the lettering of each word, concentrating mostly on people’s names. It is the idea of not just writing them but saying them aloud that is so attractive. The picture of Darbishire struggling to say Erihsibrad makes you begin to move your own lips. Jennings backwards is also particularly difficult to accomplish.

“And when they tried, with reversed spellings, to talk about Bromwich and Thompson, the air rang with guttural grunts and frog-like croaks.”

The challenge is irresistible. I am still trying to say it right as I type this now. Similarly, a chapter later, something is wrong with the bike hired by Darbishire. He diagnoses the problem as, “My back, brake-block is broken” and realises he has inadvertently devised a tongue-twister. Go on – try it. Faster ! Faster ! A brief mention should also be made of how appalled Jennings feels when the proprietor of the bike-shop, anxious about getting his money, talks about “highering” the already enormous bikes.

This free use of ambiguity, alliteration, unplanned puns is then added to by the onomatopoeia of the noises Buckeridge invents for the sounds made by the clanking machines as they produce their cacophony of noise on the way to Dunhambury. It is really a disguised English lesson about literary devices with the drudgery taken out it.

To quote many further examples of this sort of word-play would be unfair on readers new to the book. However, before we move on from the small details that are done so well, it is necessary to mention one of the most prominent features which is the delight and mystification that the boys in the books find with what can only be called “literalism”. Thus, in one Jennings story, the members of Dormitory 6 are enchanted by the concept of Mathematics being a language of its own and simulate being professors of that subject gabbling away in signs and co-sines and squares on the hypotenuse. Boys misunderstood other boys. Boys misunderstand masters and masters misunderstand boys. The inability to grasp new words immediately leads to their comic misrepresentation with Jennings’ “panache” coming out as “ashpan” when Darbishire tries to talk about it. This sort of blunder is not confined to the scholars at Linbury Court for Mr. Wilkins, with his bull-in-a-china-shop enthusiasm, tumbles to many delightful slips of the tongue with his attempts to render the name of the wayside station Pottlewhistle Halt being particularly rewarding in this area.

However, we must not underestimate the craftsmanship that has gone into constructing the plots of each of these books. The time scheme is normally set at the length of a term – in the case of “Jennings’ Diary” it is the Easter term. (That’s why they are wearing raincoats on the fragment of dust-jacket that remains to me.) Events are either developed in detail or telescoped with ease so that the climax of each book is reached as the last few days of term arrive. However, along the way, Buckeridge manages to create smaller complete episodes within the overall framework.

The theme of the diary runs throughout the whole of the book and is brought to a satisfactory conclusion. Earlier the plot in which Jennings tries to find a suitable present to reward Matron for being so nice to him when he felt ill is balanced by Mr. Wilkins’ desire to apologise to her for arguing over her decision to excuse that particular pupil from one of his detentions. Both want to give gifts. How they end up giving the gift that the other intended to provide (flowers and a cut-glass vase) is a masterpiece of comic irony. The episode concludes and the reader is able to put the book to one side after a substantial stretch of writing is brought to a neat conclusion or, much more likely, plunge into the next escapade as the butterfly minds of the boys quickly flutter on to the subject of collecting exhibits for their own museum.

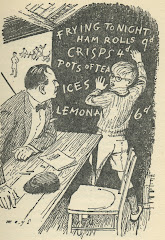

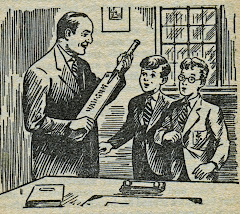

All the books have plots which are carefully dovetailed into each other in this way and most build to a crescendo of fiascos and excitement as the end of the term draws near. Buckeridge has the agility to move from the sublime to the ridiculous in a very short space of time. Thus we have the curator of the Dunhambury museum gravely discussing the corporation dustcart wheel and then Mr. Wilkins, attempting to stand on his dignity, (as per the picture) but condemned to walk the streets of the little town with an entourage of interested little boys and stray dogs whilst wheeling the offending article back to the bus stop.

Of course another feature is the dialogue of each book. Jennings and Darbishire live in a world of perpetual exaggeration and hyperbole. Nobody merely loses their temper – they go off into a “supersonic bate”. No mistakes are made but there are lots of “frantic bishes” which cause Mr. Wilkins to go in for “roof-level” attacks. Even the exclamations of dismay have an unrivalled colour to them. After all, have you ever heard anyone say, “Petrified Paintpots !” or “Fossilised fish-hooks !” ?

The skill with which the author depicts one of Mr. Wilkins’ lessons gradually going astray, reminds us all of the over-hearty laughter that occurs when a pupil makes a feeble joke or the teacher says something that seems to be wilfully understood by an innocent member of the class. After a while we too, like Jennings, Darbishire, Venables and Atkinson, are waiting for Mr. Wilkins to go “Cor-wumph” or to accuse his latest victim of talking “trumpery moonshine.” Just because we can see it coming doesn’t mean we don’t enjoy it. In fact each book is riddled with familiar “catch-phrases” that we await with eager anticipation.

He also includes the sort of remorseless schoolboy logic that turns the name Temple into the nickname Bod. You’ve forgotten it ? Well, Temple’s initials are C.A.Temple. The cat thus suggested is turned into dog. Dog is short for dogsbody and this in turn is clipped back to “Bod”. This fertility of the writer’s imagination, or this very good memory of his experiences as a schoolteacher, means that each book in the series is crammed full of examples of this sort of verbal agility that it is a delight to track down.

Even the minor characters have their place in the mini-world of Linbury Court. From Binns Minor (inevitably Snnib Ronim in the famous diary) and Blotwell, the youngest of the 79 boys in the school, to Old Nighty (the night caretaker) and, just as inevitably Old Pyjams (the day caretaker), Buckeridge manages to make them all contribute. It is a safe world, by and large, with even the outsiders like irate policeman or incompetent thieves and confused firemen, presenting a largely benevolent face to the reader. In spite of the spate of crazes that pass through its doors (from voyaging into space or becoming hut dwellers), it is also basically a timeless world and a happy world. And that is why it has lasted so well.

The inventiveness of the writer, the exuberance of the children depicted, the care lavished on the structure of each book - all surprise you anew when you take a return trip to a small part of Sussex that is forever Jennings and Anthony Buckeridge.

No comments:

Post a Comment